Startups and other organizations frequently offer two primary kinds of stock options as part of their compensation packages for employees: Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) and Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs). In addition to these, companies may present other forms of equity-based rewards such as Restricted Stock Awards (RSAs) and Restricted Stock Units (RSUs). Each of these comes with its own tax implications as set forth by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This guide focuses on the intricacies of NSOs.

What You Will Learn:

- Understanding NSOs

- Taxation of NSOs

- How to exercise NSOs

What are Non-Qualified Stock Options?

Unlike ISOs, which offer tax advantages, Non-Qualified Stock Options (often abbreviated as NSOs or NQSOs) don’t come with preferential tax treatment. Apart from employees, NSOs can also be awarded to freelancers, advisors, and external board members. While ISOs are generally tax-free upon exercise, NSOs will usually incur taxes both when you buy the shares (exercise the options) and when you sell them.

With NSOs, you gain the right to purchase a predetermined number of shares at a specific price, commonly referred to as the strike, grant, or exercise price. The company’s 409A valuation or Fair Market Value (FMV) sets this price. If the share’s value rises over time, you stand to profit from the difference (known as the ‘spread’) between the fixed purchase price and the price at which you sell the shares.

Tax Implications of NSOs

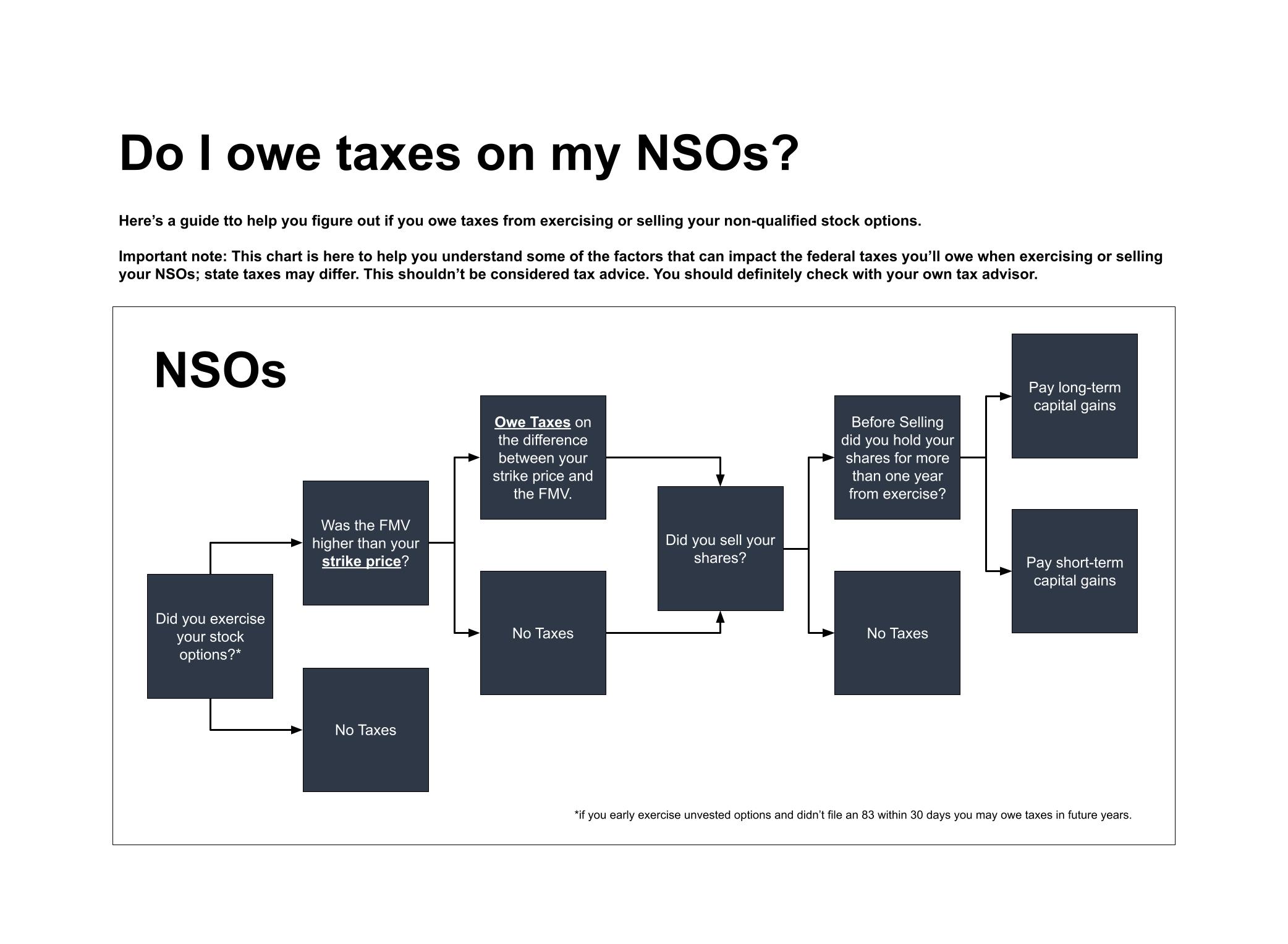

When you exercise NSOs, you’ll owe taxes on the spread, i.e., the difference between the strike price and the current FMV. If you’re an employee, the company will typically withhold the requisite income tax at the time of exercise. As a freelancer or advisor, you’ll need to make tax payments directly to the IRS.

For example, if you exercise 100 vested options with a grant price of $1 and the shares are now worth $2, you’ll incur taxes on the $100 gain.

Selling Your NSOs

After exercising the options, you have the choice of immediately selling the shares or holding them. Selling them right away means you’ll pay ordinary income tax on the spread and avoid capital gains tax. If you sell within a year, you’ll pay short-term capital gains tax on any profits. If you hold for more than a year, you’ll benefit from the lower long-term capital gains tax rate.

Qualified Small Business Stock Exclusion

If you hold onto NSO-derived stock for at least five years, you might qualify for the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) exclusion, which would allow you to sell the stock without facing federal capital gains taxes, under certain conditions.

Tax Summary:

Exercising NSOs: Expect to pay ordinary income tax on the spread.

Immediate Sale: Ordinary income tax applies on the spread.

Selling within a year: Subject to short-term capital gains tax.

Selling after one year: Eligible for long-term capital gains tax.

Selling after five years: May qualify for QSBS exclusion, potentially owing no federal capital gains tax.

When to Exercise NSOs

The opportunity to exercise your NSOs generally occurs according to a set vesting schedule. You can exercise them as soon as they vest, or choose not to. Payment options may include cash or a ‘cashless’ exercise, where a portion of your shares covers the exercise cost.

If you leave the company, a post-termination exercise period (PTEP) often applies, giving you a limited timeframe to exercise your vested NSOs. Failing to act within this period means losing the opportunity.

To optimize your financial outcome, consult a tax advisor before exercising or selling your NSOs. While they can’t forecast your company’s stock performance, they can help you strategize to minimize your tax burden.